Urban football, shiny stadiums and the quiet mechanics of gentrification

Football stadiums are sold to the public as temples of passion and engines of “revitalization”, but in practice they often work as precise tools of urban gentrification. When a city announces a new arena or a major renovation, it is rarely just about sports: it is about land value, zoning changes and new flows of capital. In the last two decades, more than 150 large football venues in Europe and Latin America have been rebuilt or heavily modernized, and in most cases the surrounding land values grew between 15% and 40% in the first five years. That jump is not neutral: it pushes tenants out, attracts speculative capital and reshapes entire districts around a new demographic, usually wealthier and less rooted in local community life.

How stadium-led gentrification actually works on the ground

The process usually starts long before the first stone is laid. City governments and clubs negotiate public guarantees, transport upgrades and planning exceptions; this package is then used to sell “proyectos de renovación urbana alrededor de estadios de fútbol” to investors. Developers buy old warehouses, modest apartment blocks and vacant plots, assuming that once the stadium is finished, demand for offices, hotels, retail and high-end housing will explode. Even simple announcements can trigger price hikes: empirical studies in Madrid, Turin and Porto show abnormal growth of land prices within 1–1.5 km of announced stadium projects, often before a single building permit is granted. That anticipation effect is the first clear sign that speculation, not community need, is steering the urban change.

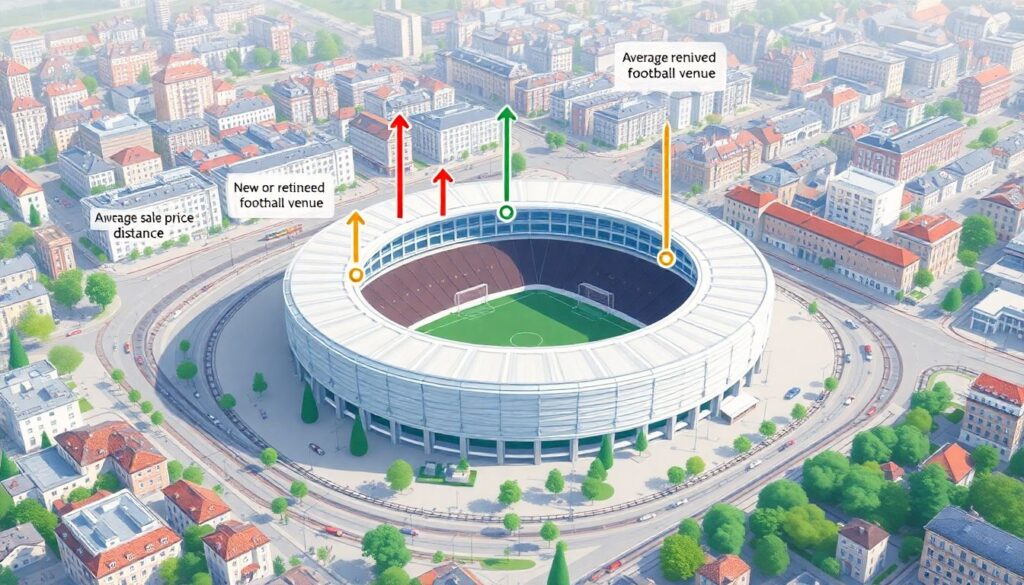

Statistics: what data tells us about prices, displacement and returns

Recent research on the “impact of nuevos estadios en precios de vivienda urbana” points to a consistent pattern. In European cities with dense public transport networks, average sale prices within walking distance of new or fully renovated football venues rose between 20% and 50% over ten years, compared with citywide growth of 10% to 25%. Rent increases were even sharper, often 5 to 10 percentage points above the municipal average. In Latin American metropolises the effect is more uneven but still strong in formal housing markets, where gated communities and mixed‑use complexes cluster near stadiums tied to international tournaments. For original residents, especially those with informal rental agreements or low incomes, this statistical uptick translates into a concrete risk: eviction, forced relocation to peripheral zones and a break in social networks that were built over decades.

Investment logic: why property capital loves stadium districts

From the viewpoint of capital, a football arena is a long‑term anchor-tenancy machine: it guarantees periodic massive footfall, anchors branding and justifies new infrastructure. That is why “inversión inmobiliaria cerca de estadios de fútbol” has become a specialized niche for funds and family offices. Stadiums de‑risk surrounding real estate because they lock in public commitments to transport, policing and public space maintenance. Even if the club’s sporting results fluctuate, the land does not move and the area remains highly visible in media narratives, which is exactly what speculative developers want. In many cities, you can trace the same playbook: acquire cheap land under the promise of “urban regeneration”, lobby for up‑zoning and tax incentives, then offload premium offices and apartments to institutional investors once the area’s reputation flips from “degraded” to “vibrant”.

Practical perspective: what this means for people who live, rent and buy

For current residents, especially renters, the most practical implication is timing. The most aggressive phase of speculation usually occurs between the official stadium announcement and the second or third season after opening. During that window, landlords test the market with sharp rent increases and conversion of long‑term leases into short‑stay or tourist rentals. If you rent in a neighborhood targeted by a big club’s expansion, proactively checking your lease conditions, renewal deadlines and local tenant‑protection rules becomes essential. Organizing with neighbors to monitor evictions and push for rent caps or social housing quotas linked to the project can slow down displacement. Waiting passively often means discovering, too late, that your building has been sold to a fund with a clear plan to renovate and upscale each unit.

At the same time, some middle‑income households are tempted by the “cool factor” and the promise of future gains when considering the “compra de pisos en barrios próximos a estadios de fútbol”. This can be rational, but only if risks are assessed soberly. Stadium districts bring noise, crowding and security restrictions on match days; they are not uniformly desirable for long‑term residential life. Buyers should look beyond club marketing brochures and examine municipal plans: Will there be schools, health centers and green spaces, or is the area designed mainly for events, shopping and tourism? Is the local economy diversified, or is everything tied to hospitality and match‑day consumption? Practical due diligence here is less glamorous than the stadium renderings, but it is the difference between a liveable investment and an over‑priced, volatile asset.

Professional side: consultants, clubs and the urban development industry

Behind almost every large arena project is a small ecosystem of firms offering “consultoría en desarrollo inmobiliario en zonas deportivas”. Their job is to translate club ambitions and municipal narratives into spreadsheets and masterplans that appeal to financiers. Practically, this means modeling future cash flows from mixed‑use complexes, estimating how many luxury units the local market can absorb and identifying regulatory loopholes to increase density or reduce social housing obligations. For consultants who want to work ethically, the challenge is to integrate hard social indicators—displacement risk, housing affordability, access to public services—into those same models. Instead of maximizing only return on equity, they can propose phased developments, inclusionary zoning and community land trusts as part of the financial strategy, not as decorative corporate social responsibility.

For clubs and their business partners, understanding these dynamics is not just a moral question; it is a matter of long‑term legitimacy. When fans see that a new stadium comes with the erasure of long‑standing communities and the replacement of neighborhood bars by generic chains, they often react with protests and boycotts. Brand value in football is unusually dependent on emotional authenticity, and that can be damaged by aggressive real‑estate speculation. From a practical business standpoint, involving local residents in design consultations, reserving commercial spaces for traditional small businesses and committing to transparent reporting on housing impacts can mitigate backlash while still allowing viable development. The key is accepting that the stadium is not a blank slate but part of a dense urban fabric with its own history and rights.

Forecasts: how stadium‑driven gentrification may evolve

Looking ahead to the next decade, several macro‑trends are likely to intensify the use of stadiums as speculative devices. Climate adaptation policies will push cities to redevelop obsolete industrial and port areas, many of which are already earmarked for sports and entertainment complexes. At the same time, global capital searching for yield in a low‑interest‑rate environment will continue to see stadium‑adjacent assets as attractive, especially when backed by long concession contracts and naming‑rights deals. Digital ticketing, dynamic pricing and data‑driven fan engagement will increase the monetization potential of match‑day and non‑match‑day events, further justifying high land valuations. Without countervailing regulation, these drivers imply deeper social stratification: premium districts orbiting club infrastructures and increasingly precarious peripheries absorbing displaced residents.

However, political and social resistance is also likely to grow. Cities such as Lisbon, Buenos Aires and Berlin are already experimenting with stricter rules tying large sports investments to affordable housing quotas and participatory planning. Over the next years we can expect more legal challenges, citizen referendums and conditional public financing, especially after high‑profile controversies around mega‑events. For practitioners—lawyers, planners, activists—this is a window of opportunity to design concrete tools: impact‑fee schemes dedicated to social housing, anti‑eviction moratoria during large construction phases, and binding community‑benefit agreements attached to stadium concessions. The balance between speculative gain and social value is not predetermined; it will be shaped by the policies and alliances built in this transitional phase.

Impact on the wider real‑estate and football industries

The interplay between football and property markets is reshaping both sectors. For real‑estate players, stadiums function as branding platforms and risk‑sharing mechanisms, allowing them to package mixed‑use developments as lifestyle products linked to the emotional universe of a club. This logic seeps into financing, where real‑estate investment trusts and infrastructure funds co‑invest in “sports‑anchored districts”, blurring the line between civic infrastructure and private leisure. On the football side, clubs increasingly act as urban developers, managing portfolios of hotels, offices and residential towers rather than focusing solely on sporting performance. That shift changes internal expertise: boards recruit real‑estate specialists, negotiate with mayors and banks and think in 30‑year land cycles, not only in annual league calendars.

For the industry as a whole, the long‑term risk is over‑exposure to property cycles. If too much of a club’s financial stability depends on stadium‑area rents and commercial uptake, an economic downturn or oversupply of retail and offices can quickly undermine balance sheets. Conversely, cities that tie too much of their “revitalization” strategies to sport‑led megaprojects become vulnerable to shifts in fan behavior, broadcasting deals and tourism flows. Practically, diversification is vital: both urban and football policymakers should avoid monocultures of entertainment and speculative housing, and instead mix stadium investments with support for small‑scale, distributed urban projects. Recognizing football arenas as powerful but double‑edged tools of gentrification is the first step toward using them in ways that serve residents, not just balance sheets.